Autistic characters are nothing new.

I can identify at least one autistic character in nearly every show or movie I watch.

It’s not like it’s hard…it’s about who I relate to most and who I see me in.

Deliberately writing autistic characters, though? I can see that being hard.

Especially when bad autistic representation is no longer acceptable representation.

As an autistic person, writing autistic characters comes naturally to me, so these are my best tips based on what I’d like to see in autistic characters by allistics.

(Thankfully autism isn’t as complex as DID!)

What to avoid

Non-autistic writers often want to include autistic characters in their stories to say,

“Look at this autistic character. Look how lovely they are. They’re ‘normal’ like you and me. They’re just people!”

This is assimilationist representation.

The goal is to reassure non-autistic audiences the autistic character is “just like everyone else”.

Make the traits less annoying, minimize their disability, center neurotypical comfort and you have palatability politics.

Marginalized characters become “safe”, “gentle” or “non-threatening” for the dominant group.

This is an example of the neurotypical gaze, where you have neurodivergent (ND) characters written for neurotypical approval, not authentic representation.

Inspiration porn happens when the autistic character’s existence/influence/journey is meant to make allistic characters feel good.

Accept autistic people as autistic people.

Before you can respectfully write about autism, you need to accept autistic people.

This means accepting us as autistic people, not “normal people” with autistic traits.

Thinking about autistic traits neutrally rather than negatively.

The entire point of an autism diagnosis is that autistic people are NOT non-autistic people.

Having an autistic coworker who does their job is not special. If you’re surprised, that’s because you’ve been conditioned to align with negative stereotypes.

Maybe you even “forget” they’re autistic until you come face-to-face with an autistic trait.

Especially if they’re an adult, even though you think they’re a bit “childish”.

That’s like saying you “forget” a Black coworker is Black because they’re not like your stereotypes.

Truly accepting autistic people when you’re not accustomed to being around autistics is uncomfortable. It’s challenging.

That’s by societal design.

Autistic people used to be hidden, institutionalized, murdered…now, we’re active citizens of society.

Learn how to look at autistic people without seeing autism spectrum disorder — without “disorder” even coming to mind.

Because the way non-autistic people look at autistics? That’s how autistics learn to perceive allistics, asking ourselves how WE are the “disordered” ones when non-autistic communication makes so little sense.

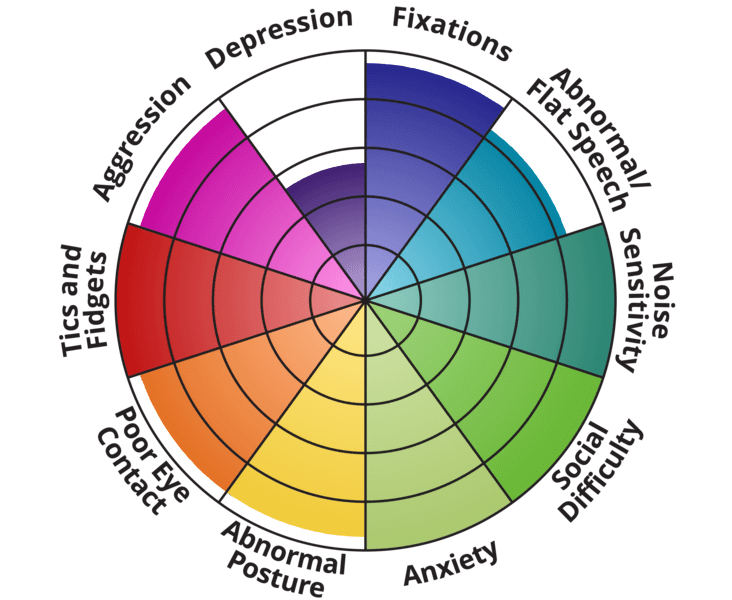

Be aware of the spectrum.

You can’t represent autism entirely. Autism is a spectrum.

It’s so broad that autism cannot be encompassed in one character.

You’re not going to be able to represent autism in its entirety in only one character.

You don’t need to, either; it’s not realistic.

Heartbreak High’s Quinni is one of the best autistic characters I’ve ever come across. She’s perfect as she is. She’s the perfect bundle of autism representation I’ve ever seen.

The only other best autistic character I’ve known was Snowcake’s Linda Freeman, who wasn’t played by an autistic actress (however great Sigourney Weaver was).

Quinni’s character exhibits autistic traits for her and has some extremely autistic experiences. Notice how not all the autistic traits are applied to her.

She has her routine and some accommodations, which help her navigate life in a way the non-autistic viewers don’t find her “that” autistic — but the more stress she experiences, the “more” autistic she does seem.

A character’s autism needs not be front-and-center, but you do need to understand that autism can dictate how one behaves around other people and even alone.

Autism affects how people perceive the world around them.

For all purposes, autism does define part of a person. However, that person doesn’t have to take on their autism as part of their personality by developing a special interest in autism.

Base your autistic characters on actually autistic people.

Like, real-life autistic people you can ask questions — ones who know you’re seeking to include an autistic character in your story and are okay with it.

This will help you create a much better autistic character who feels real because they are real.

That said, don’t seek out an autistic person who seems “obviously autistic” because they also have co-occurring conditions that use autism as an umbrella term.

Autism is autism. Co-occurring conditions can and do affect autistic people, but autism is not an umbrella term.

This reinforces harmful stereotypes and prevents autistic people from receiving help, support and kindness.

Be real if you want realistic representation.

Non-autistic people are often annoyed by autistics.

Autistic people may find fellow autistics annoying. They definitely find non-autistics annoying.

Some autistic people pride themselves in saying, “I’m not like those kinds of autistic people.”

There are icky, judgmental behaviors everyone engages in — especially when it comes to people who are different, especially if someone doesn’t understand those differences.

Non-autistic people who’ve not spent enough time with mild-to-low-masking autistic people make thin-slice judgments about autistic people.

This reality introduced to fiction attracts criticisms on how “everything is so political these days”. Well, that’s because politics is life.

Research autistic-coded movie and TV show characters, and read what people say about them.

Search “[character name] problematic” and “[character name] annoying” if you’re struggling to empathize with autistics.

Moral scrupulosity OCD

A trait autistic people occasionally slip into is moral perfectionism. They feel they need to be morally perfect/right to be a “good” person.

They may even hold other people to this expectation. Some autistic content creators with loads of followers engage in this often, especially targeting other autistic people.

When people with moral perfectionism think your perspective is wrong or too nuanced/not nuanced enough, they project that standard onto you.

Some autistic people think dichotomously, a cognitive distortion that can also be a symptom of PTSD.

Trauma’s quite common in autistic people.

When the behavior becomes a pattern, it dips into condition territory — a type of OCD.

Learn about the internal experiences of autistic people.

Autistic people experience life oftentimes by our senses.

I’m extremely affected by the sensory input of an environment — how it smells, feels, tastes, sounds.

If an environment is too much, I dip. I can’t tolerate it. This is my life and how autism affects my life — not a choice. It’s how my brain processes sensory information.

Non-autistic people seem to be able to tolerate sensory overload, like it’s not causing them so much pain they can’t tolerate their shoes.

If music is too loud, I can’t tolerate wearing my sweater.

Not to mention the catastrophizing and looping that happens in my head because of pattern recognition and me trying to make sense of interactions/inescapable situations.

If I see an autistic character sit in a car and start driving like it’s nothing — and nowhere in their arc is their system/struggle to drive/finding accommodations that help them do that — I’m going to think, “Ah, this is the palatable autistic character.”

Special interests are life. Not all special interests are socially appropriate and can sometimes be a person.

You could just say they’re autistic.

I create autistic characters without realizing it, probably because I’m autistic.

My characters who are meant to be non-autistic are non-autistic in my head, therefore they are in the story…even if they do have some autistic traits.

If you say a character is autistic, but they don’t come across that way to other autistics, there’s a problem.

However, if autistic people relate to the character, you could say, “They’re autistic.”

But don’t do the wishy-washy representation of “if you’re autistic and relate to them, yeah, they’re autistic; if not, then they’re not”.

I’m not unpacking that, but it’s problematic.

You could also create a character who winds up feeling autistic-coded, without even realizing it.

Perhaps this is a reason to have beta readers from different backgrounds and neurotypes prior to publishing the book.

Leave a comment